Topology (2nd Edition)

This book is the best introductory book on Topology, an upper undergraduate/graduate course taken in university. I have written a short book review on it.

Excerpt:

Book Review: Topology

Book’s Author: James R. Munkres

Title: Topology

Prentice Hall, Second Edition, 2000

It is often said that one must not judge a book by its cover. The book with a plain cover, simply titled “Topology”, is truly a rare gem and in a class of its own among Topology books.

One striking aspect of the book is that it is almost entirely self-contained. As stated in the preface, there are no formal subject matter prerequisites for studying most of the book. The author begins with a chapter on Set Theory and Logic which covers necessary concepts like DeMorgan’s laws, Countable and Uncountable Sets, and the Axiom of Choice.

The first part of the book is on General Topology. The second part of the book is on Algebraic Topology. The book covers Topological Spaces and Continuous Functions, Connectedness and Compactness, and Separation Axioms. Some other material in the book include the Tychonoff Theorem, Metrization Theorems and Paracompactness, Complete Metric Spaces and Function Spaces, and Baire Spaces and Dimension Theory.

The book defines connectedness as follows: The space  is said to be connected if there does not exist a separation of

is said to be connected if there does not exist a separation of  . (A separation of

. (A separation of  is defined to be a pair

is defined to be a pair  ,

,  of disjoint nonempty open subsets of

of disjoint nonempty open subsets of  whose union is

whose union is  .) Other sources may define connectedness by,

.) Other sources may define connectedness by,  is connected if

is connected if  continuous

continuous  .

.

Also, the proof of Urysohn’s Lemma in the book was presented slightly differently from other books as they did not use dyadic rationals to index the family of open sets. Rather, the book lets  be the set of all rational numbers in the interval

be the set of all rational numbers in the interval ![[0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=1a1a1a&s=0&c=20201002) , and since

, and since  is countable, one can use induction to define the open sets

is countable, one can use induction to define the open sets  . In hindsight, the dyadic rationals approach in other sources may be more explicit and clearer.

. In hindsight, the dyadic rationals approach in other sources may be more explicit and clearer.

An interesting new concept mentioned in the book is that of locally connectedness (not to be confused with locally path connectedness). A space  is said to be locally connected at

is said to be locally connected at  if for every neighborhood

if for every neighborhood  of

of  , there is a connected neighborhood

, there is a connected neighborhood  of

of  contained in

contained in  . If

. If  is locally connected at each of its points, it is said simply to be locally connected. For example, the subspace

is locally connected at each of its points, it is said simply to be locally connected. For example, the subspace ![[-1,0)\cup (0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B-1%2C0%29%5Ccup+%280%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=1a1a1a&s=0&c=20201002) of

of  is not connected, but it is locally connected. The topologists’ sine curve is connected but not locally connected.

is not connected, but it is locally connected. The topologists’ sine curve is connected but not locally connected.

In general, the content of the book is comprehensive. The other book, “Essential Topology”, did not cover some topics like the Urysohn Lemma, regular spaces and normal spaces.

Approach

The author’s approach is generally to give a short motivation of the concept, followed by definitions and then theorems and proofs. Examples are interspersed in between the text. The motivation tends to be a little bit too short though. For instance, in other books there is some motivation of how balls can determine the metric in a metric space, leading to the concepts of “candidate balls”  . This useful concept is not found in the book Topology, nor the other book Essential Topology.

. This useful concept is not found in the book Topology, nor the other book Essential Topology.

One interesting explanation of the terminology “finer” and “coarser” is found in the book. The idea is that a topological space is like “a truckload full of gravel”‘ — the pebbles and all unions of collections of pebbles being the open sets. If now we smash the pebbles into smaller ones, the collection of open sets has been enlarged, and the topology, like the gravel, is said to have been made finer by the operation.

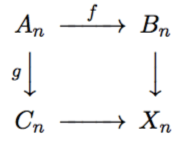

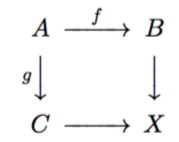

Another point to note is that the book does not use Category Theory. Personally, I would prefer the Category approach, since it can make proofs neater, and it provides additional insight to the nature of the theorem. We also note that the other book “Essential Topology”, also does not explicitly use Category Theory. But upon closer examination, the book has expressed commutative diagrams in words, which is not as clear as in diagram form.

Organization

The organization of the book is similar to most other books, except that it covers Connectedness and Compactness before the Separation Axioms. The concept of Hausdorff spaces, however, is covered way earlier, immediately after the discussion of closure and interior of a set. This enables theorems like “Every compact subspace of a Hausdorff space is closed” to be proved in the Compactness chapter.

Style

The author’s style is to combine rigor in proofs and definitions, with intuitive ideas in the examples and commentary. This makes it both a good textbook to learn from, and a good reference for proofs too.

This informal style in the commentary makes for a especially good read. For instance, a mathematical riddle is mentioned: “How is a set different from a door?” (For interested readers, the answer can be found on page 93.)

Also, there are many figures in the book, 84 sets of figures to be precise. This is rather good for a math book, and I would recommend the book to visual learners.

However, to learn Topology from this book alone may be difficult. Even though there are exercises to practice, there are no solutions and very few hints. Also, the book uses the terminology “limit point”, which can be confusing.

The book has surprisingly few typographical errors. While reading through the book, I only spotted a trivial one on page 107, where a function written as “ ” should be “

” should be “ ” instead. Upon consulting an errata list, there was only one page of errors.

” instead. Upon consulting an errata list, there was only one page of errors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite some shortcomings of the book, Topology is a great book, and if there was one Topology book that I could bring to a desert island, it would be this one.

Chapter Headings

Part I: General Topology

- Set Theory and Logic

- Topological Spaces and Continuous Functions

- Connectedness and Compactness

- Countability and Separation Axioms

- The Tychonoff Theorem

- Metrization Theorems and Paracompactness

- Complete Metric Spaces and Function Spaces

- Baire Spaces and Dimension Theory

Part II: Algebraic Topology

- The Fundamental Group

- Separation Theorems in the Plane

- The Seifert-van Kampen Theorem

- Classification of Surfaces

- Classification of Covering Spaces

- Applications to Group Theory

For more undergraduate Math book recommendations, check out Undergraduate Level Math Book Recommendations.

is said to be compactly generated if it satisfies the condition: A subspace

is closed in

if and only if

is closed in

for all compact subspaces

. A compactly generated Hausdorff space is a compactly generated space which is also Hausdorff.