(Continued from https://mathtuition88.com/2015/06/20/what-is-a-measure-measure-theory/)

Lemma: Let  be a measure defined on a

be a measure defined on a  -algebra X.

-algebra X.

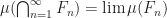

(a) If ( ) is an increasing sequence in X, then

) is an increasing sequence in X, then

(b) If  ) is a decreasing sequence in X and if

) is a decreasing sequence in X and if  , then

, then

Note: An increasing sequence of sets ( ) means that for all natural numbers n,

) means that for all natural numbers n,  . A decreasing sequence means the opposite, i.e.

. A decreasing sequence means the opposite, i.e.  .

.

Proof: (Elaboration of the proof given in Bartle’s book)

(a) First we note that if  for some n, then both sides of the equation are

for some n, then both sides of the equation are  , and inequality holds. Henceforth, we can just consider the case

, and inequality holds. Henceforth, we can just consider the case  for all n.

for all n.

Let  and

and  for n>1. Then

for n>1. Then  is a disjoint sequence of sets in X such that

is a disjoint sequence of sets in X such that

,

,

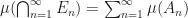

Since  is countably additive,

is countably additive,

(since (

(since ( ) is a disjoint sequence of sets)

) is a disjoint sequence of sets)

By an earlier lemma  , we have that

, we have that  for n>1, so the finite series on the right side telescopes to become

for n>1, so the finite series on the right side telescopes to become

Thus, we indeed have proved (a).

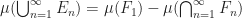

For part (b), let  , so that

, so that  is an increasing sequence of sets in X.

is an increasing sequence of sets in X.

We can then apply the results of part (a).

![\begin{aligned} \mu (\bigcup_{n=1}^\infty E_n) &=\lim \mu (E_n)\\ &=\lim [\mu (F_1)-\mu (F_n)]\\ &=\mu (F_1) -\lim \mu (F_n) \end{aligned}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cbegin%7Baligned%7D++++%5Cmu+%28%5Cbigcup_%7Bn%3D1%7D%5E%5Cinfty+E_n%29+%26%3D%5Clim+%5Cmu+%28E_n%29%5C%5C++++%26%3D%5Clim+%5B%5Cmu+%28F_1%29-%5Cmu+%28F_n%29%5D%5C%5C++++%26%3D%5Cmu+%28F_1%29+-%5Clim+%5Cmu+%28F_n%29++++%5Cend%7Baligned%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=1a1a1a&s=0&c=20201002)

Since we have  , it follows that

, it follows that

Comparing the above two equations, we get our desired result, i.e.  .

.

Reference:

The Elements of Integration and Lebesgue Measure

be a measure space. Let

and

. Prove that there exists a set

with

, such that

.

be a simple function such that

.

. Note that

. Hence each nonzero value of

can only be on a set of finite measure. Since

has only finitely many values,

.